My new home on the web is ThereseArkenberg.com--the same information (polished and updated) but in a different format. I'm still blogging, reviewing books, publishing short stories, sharing advice about copyediting, and who knows what I'll be up to next?

Thank you for following along!

Story Addict

Therese Arkenberg's home on the web

Monday, August 21, 2017

Sunday, March 13, 2016

Words to (Almost Always) Cut

Strong stories are not necessarily short. They don't need to be Hemingway-esque masterpieces of bare prose. In fact, I have friends who would argue "Hemingway-esque masterpiece" is an oxymoron; the man's writing gets downright boring. And it would be hypocritical of me to argue for only short sentences or short paragraphs. I have to consciously apply myself to make use of either.

But in a strong story, every word counts. And no word is misplaced or ill-chosen. The vocabulary is vivid and usually varied, plus precise (though alliteration is optional). Words do not undermine or contradict their neighbors, and sentences flow well, not being fatiguing or confusing to read.

This is not the case in many, probably most, early drafts. When the writer's energies are focused on figuring out what the story is and what order to tell it in, they can't stop to worry about how many times they've used the word "almost" on one page. But an editor--whether a professional copyeditor, a beta reader doing their friend a favor, or an author revising their own work--would be remiss not to look out for these superfluous words, particularly because they're so common. Certain ones appear again and again as the culprits weakening an image or confounding a text, enough that I can create a handy wanted list for any writer to look out for. When I'm reading a page and the prose sounds subtly off to me, I reread again with an eye for these problem words, and I usually find one or more of them.

A number of the words on this list may be familiar to people who have read my earlier blog posts. This is a sign of just how common an issue they are, appearing in manuscripts by all kinds of writers in many different genres. It bears repeating how much they shouldn't be frequently repeated. Which doesn't mean they can never be used--all words have a purpose. Using them more mindfully, though, will improve most manuscripts.

Catching Problem Words

As you begin your line edit (after any major changes to plot, since you don't want to fiddle with words in a scene that gets entirely rewritten or cut later on), you can set your manuscript to highlight any of the words on the list below. This provides an immediate graphic representation of how often they appear, and how close together.

If you want you, can literally highlight them. Using Word's Find/Replace option, enter each word (or words, including alternative forms, conjugations, or synonyms) and replace it with itself, highlighted. Highlighting is found under the "format" drop down menu. Pick a color you like, because you're going to see plenty of it.

If highlighting gives you eyestrain, there are other options. Some writers replace the word with itself IN ALL CAPS, which can be just as eye-catching. You return a word to normal, should you choose to keep it, by selecting it and pressing Shift + F3.

Returning words to normal is also made easy with Tracked Changes. With Tracked Changes on, I find the word but leave the "Replace" bar empty, so that the target is in effect deleted from the manuscript. Tracked Changes shows this as the original word being struck through. Each time I decide I really do want to keep it--because, again, these words have their uses--I need to either reject my deletion or manually retype. Okay, it's not super easy. That would go against the point of this exercise, which is to make these words stand out for decimation (if you're lucky enough to only overuse them by 10%) or culling (for the rest of us).

Cut These Words

1. Almost

Yes, it is included in this post title with my tongue in cheek, but also because almost, like every other word on this list, it can be kept sometimes. Literature deals with ambiguous situations, unreliable narrators, and inexact cases where absolute word choice would be inaccurate. There's a world of difference between I almost missed the train and I missed the train!

However, writers may be impressed to see just how often "almost" goes without being said. There are also times where another word would fit better without needing to be qualified as "almost" so.

She was almost sad about his retirement could be She was disappointed to hear of his retirement or She was sad about his retirement.

Unless the focus is on the near-miss nature of a circumstance or event, "almost" can prove unnecessary. Take it out of your writing and see.

This issue also arises with similar phrases like "kind of," "sort of," and "a bit."

2. He said [and]

Only the most avant-garde manuscript would do away with dialogue tags entirely. And neither do I want to encourage writers to replace all the "said"s in their work with more "interesting" synonyms.

However, not all "said"s are required. I especially want to point out a tendency in some first drafts where dialogue tags are made redundant by character action beats that already identify the speaker.

"It's a bust," Sam said and shook his head.

Why not: "It's a bust." Sam shook his head.

There are reasons why not, such as keeping the rhythm of the extra two words. Or if an "interesting" dialogue tag is also needed to give the right picture: "It's a bust," Sam sobbed, shaking his head.

Note how even in that example I can't resit replacing the "said and" with a slightly less wordy alternative. The occasional "he said and" is a minor sin at worst. However, frequent and clumsy tagging can distract attention from the actual dialogue. If a manuscript is using a lot of dialogue tags, to the point that it becomes noticeable as an editor reads or rereads it, it's worth some extra examination.

3. "Actually" or "really"

These words definitely have their place (so does "definitely," their cousin). Yes, really!

But actually, in most writing it is assumed that the things being described really, actually happened in the world of the story. Unless it's in-character for the narrator or speaker to stress what they're saying by peppering in these adverbs, consider if they can be taken for granted. There's a risk otherwise of protesting too much and sounding sarcastic with their implied incredulity.

I realized you were actually good at this copyediting thing. I'm really grateful to hear you say that, italicized example text.

If "actually" is appearing multiple times on each page, I suspect the writer is worried about overcoming suspension of disbelief in their story (at least it is in my case when I overuse the word). Subconsciously, they overcompensate. To them, I say: try taking out your insistent adverbs and see how confident your prose will sound without them! Because it will. It really, actually, definitely will.

4. Just

This is a common word for a reason. Most people use it at some point during their day, and it's helpful to communicate casualness and "no pressure"--or the opposite. "Just one minute!"

It's just been a long day has a different tone than It's been a long day.

However, if you've already said I'm just tired and I just need to lie down for just five minutes, the difference in tone becomes negligible.

A few "just"s go a long way, and they tend to appear in packs. Even when each individual instance works perfectly, consider cutting the less essential ones to avoid readers getting distracted by the repetitive rhythm and over-casual (bordering on indifferent) tone that builds up when every other sentence is "just" this or that.

5. Always

The other word in the title of this post. It's rarer for this one to be overused, but sometimes authors will have passages talking about how their characters "always would" do this or that. Useful background information for a well-rounded cast? Sure. It can be a problem if it segues into telling over showing, or if it's unclear how the minutely depicted routine is relevant.

Additionally, sometimes "always would" adds distance where it isn't needed.

Uncle Bob always would take us fly fishing in summer lacks the immediacy of Uncle Bob took us fly fishing every summer.

In fact, "would" is a word to highlight too if you find yourself often talking about things that aren't happening directly in the story. It's a more complicated issue than overusing particular words in themselves--it's more about where the action and focus is. Even when narrating things that aren't happening onscreen, look for phrases that make them feel vivid and immediate.

When "would" is overused, it also sounds awkward.

When Sarah would pick me up for soccer practice, she would stick her head out of the moon roof and holler my name so loud the entire neighborhood would echo with her voice.

The sentence is a lot breezier without fewer "would"s:

Whenever Sarah picked me up for soccer practice, she'd stick her head out of the moon roof and holler my name so loud the entire neighborhood echoed with her voice.

6. That

According to Dictionary.com, that is a pronoun used 6 different ways, an adjective used 3 different ways, an adverb used 3 different ways, and a conjunction used 2 different ways. I can't distinguish half those uses myself. It's a word with a lot of uses, is the point I'm making.

Rather like "just" (but with even more applications), the word is so useful that it travels in packs. Resulting sentences can get awkward: I said that I knew that, but I'm touched that she cared enough that she put in the effort to do that. Not to mention vague.

It can signal unnecessary wordiness--Because of the fact that I missed the deadline can cut to the chase with Because I missed the deadline.

At other times it's a single unnecessary word: He's worried that she hates him can be He's worried she hates him. In cases like that (ha), there's no one right or wrong way to phrase it. You can keep "that" if you want and can do without it if you prefer. In some cases it makes a long sentence clearer. Yet if you're trying to cut words (perhaps you're at 1200 and the market is for flash fiction) "that" can be a painless one to target.

Speaking of pronouns and vagueness, not only 'that' but all its friends and family can sometimes get out of hand and lead to writing that is imprecise or confusing. Watch that your pronoun referent is clear. Rephrase when necessary.

7. Is

Highlight along with was, are, will be, and all other conjugations of "to be." It's possible to write without them entirely, but that's not what I'm suggesting here. (Sorry, You can write without them entirely, but I don't suggest that here.)

Prose becomes more vivid when "to be" verbs and sentences made up of them are replaced with stronger or more specific ones. It's worth trying this for a few of your sentences just to see what happens:

She was sad about his retirement becomes His retirement saddened her.

The wind was blowing through the trees becomes Trees bowed in a growing wind.

There was a beach behind the house becomes "Yes! Beachfront property!" Sal ran towards the waves.

"To be" verbs can sometimes be repackaged as adjectives (The woman was blond becomes The blond woman... doing something else in an overall more multitextured sentence about more than her hair color).

There are also various English tenses that use "to be" verbs, like the present progressive: He was running down Birch Street. These aren't bad tenses, and you should feel free to use them. However, at times when "to be" verbs are the most frequent ones on the page, consider different ways to rephrase some.

The woman was blond and the man was running down Birch Street towards her, which was forward of him in my opinion, but maybe they were familiar with each other.

Try:

The man ran down Birch Street towards the blond woman. Pretty forward of him if you ask me, but maybe they knew each other.

8. Can

A crowd could be seen out the hotel windows.

Could be seen by who? This is an unclear and inactive way to describe the presence of a crowd.

A crowd had gathered outside the hotel and their chanting carried through the windows.

I could feel my blood run cold (as one might hearing the chanting crowd) easily becomes I felt my blood run cold or, more direct still, My blood ran cold.

"Can" is often an unnecessary filter unless the focus is really on the ability to do something: After Dr. Speechgood's lessons, for the first time in my life I could appear onstage before a crowd without hyperventilating.

I use "can" in a number of places in this blog post, because I'm talking about options writers have rather than saying they must do any one thing.

However, watch out for "can"s that just add word count rather than meaning. Also be careful of similarly redundant filtering words such as "feel," "know," "think," "realize," "see," and "hear" (my examples above show how to remove a "felt" and a "seen"). Each of these words has its place, but often a sentence will work without them and focus instead on the sensation, knowledge, thoughts, realization, sight, or sound itself.

9. "Start" or "Begin"

As I researched the conspiracy, I began to get convinced of the scale of the cover-up.

Not an awful sentence, but it may cut to the chase: As I researched the conspiracy, I got convinced of the scale of the cover-up.

At the sound of the crash, I started to run across the street.

Here "started" may be more useful, because the sentence is about the sound that triggered the character's run. It still isn't essential to meaning: I ran across the street when I heard the crash.

I began to talk when my sister gently put her hand over my mouth.

Here "began" is appropriate because the action isn't completed. However, if there is no interruption, if the character both begins and completes their action, put the focus on the action instead.

I started to laugh to myself. My heart started pounding.

You save a few words by simply stating: I laughed to myself.* My heart pounded.

*Reflexive pronouns can also go unsaid for: I laughed (when the character's the only one in the room, we get the picture. If someone else is in the room, the laugh isn't private after all). In some manuscripts I highlight "to me"s.

10. And

You could probably write an entire story without it if you wanted to be experimental (sometimes I think of trying to). Still, most writers do not have a problem with using too many "and"s.

Some do, and I'm one of them.

It's part of the reason I write monstrously long sentences. I didn't notice the problem until a writing teacher pointed it out, circling all the "and"s on one of my pages. There were many, many circles. Breaking up some of those sentences, and deleting the superfluous second halves of others (I was terrified and anxious can be I was terrified), made the story much smoother to read.

Occasionally, when I find myself losing track of a paragraph, I look for the number of "and"s. Does everything in the story come in pairs, threesomes, or more? (If I'm adding or deleting Oxford commas, the "and"s become even more noticeable.) Do sentences stretch on and on, long past the point of fatigue? Is this an organized paragraph completely exploring a given topic, or is it a suitcase where every word and concept the author strikes on gets shoved in artlessly?

The "said and"s mentioned earlier can be considered a subset of "and" overuse. Related, "and" can connect two ideas that really need the breathing space of their own sentences. She kissed me for the first time last night and then confessed she murdered a man. --Unless the point of that line is to show how quickly things are moving, consider giving each of those ideas more room.

Also beware crammed lines that become bathetic: She felt her heart breaking, her eyes burning with tears, and her throat stop up, and past the pain and torment she said, "I don't know, and I'm too hurt right now to think clearly and rationally."

Other conjunctions such as "but" and "or" can also signal repetitive structure or superfluous additions. While you're scrubbing "actually"s from your prose to make it sound more convincing, I suggest you target "or something"s too. They're a warning sign for unclear thinking.

When we lost sight of your boat, I thought you'd drowned or something!

Doesn't "I thought you'd drowned" say enough?

I'll buy her a nice present, maybe flowers or something.

Stick with the concrete image: I'll buy her a nice present, maybe flowers (or chocolates).

(I'll buy her something nice, maybe flowers will also work, since it closes on the specific idea of flowers as an example of the nice somethings that might be given as gifts. It's only when a sentence goes on to be imprecise that it's weakened.)

Similarly, "somehow" and "some X" (as in "some X or another" or "some random X") should be watched for, in case they signal a fuzzy part of the story.

***

Lastly, there are classes of words that can't be easily highlighted, because they're all different, but still should be watched for.

11. Adjectives describing a character from that character's point of view

No need to get rid of these entirely, but do make sure they fit the character's voice and attitudes towards themselves. Have you noticed your raven locks or pearly smile lately? If you have, would you say so in those exact words?

Also make sure these descriptions--whether physical, mental, or emotional--come at a time that's appropriate. I knelt over my friend's body, brushing honey-blonde hair from my tear-filled eyes. This brutal and unanticipated murder had shaken my normally calm exterior.

It's a cliche to have a character stand in front of a mirror and rattle off details of their appearance, but I understand why it happens. Most of us don't think a whole lot about how we look except when we're confronted by it. If you're searching for more variety, people are also confronted by their appearance when they visit their parents and see their photos on the mantel, when they meet with their prettier siblings, when they scroll through pictures taken on their phone, and when they log in to their Blogger account and debate updating their Google Account icon.

12. "Editorializing" adjectives and adjectives that tell what has or will be show

"Editorializing" adjectives inject opinion and judgment: My cruel stepmother. My handsome but not entirely trustworthy boyfriend. My clever and glamorous girlfriend.

They have their place, but shouldn't be substitutes for full, well-rounded characterization. And if the characterization is vivid enough, these adjectives can feel distracting or patronizing to readers, who have already made their own judgments. An editorializing adjective is more useful to show the POV character's attitude than to convey new information (if the "cruel" stepmother is nothing but gracious in her actions, perhaps the narrator has a bias).

These superfluous "telling" adjectives can be minor--one I see with some frequency is when a character at a hospital and The female doctor turned to the male nurse and told him, "Make sure the patient's condition remains stable." He nodded and checked Pat's vitals as she left the room.

The pronouns effectively make it clear who is who, and to me this description seems to imply female doctors and male nurses are some different sort of species from the run of the mill doctor or nurse. If the gender is really noteworthy enough to be highlighted, that might come in dialogue, as when 90-year-old Pat exclaims "Look at that! A lady doctor! We didn't have so many of those in my day."

The issues can become more major when a mildly devious character is constantly described as "conniving," to the point that the reader feels the accusation is getting unjust or exaggerated. Or when a "shy" character accosts the protagonist and no one seems to find this unusual behavior. Or when the color of an item is repeated every time it makes an appearance, and every time the heroine blinks her eyes are described at topaz brown.

Overall, be careful of sentences crammed with adjectives and adverbs. A reader can get lost in a thicket of verbiage that gives no clear picture. It's hard to produce examples of this because it happens in aggregate, over a number of sentences or paragraphs. In general, though, every noun does not need an adjective and every verb does not need an adverb. If they get them anyway, the prose begins to pick up a rhythm that distracts from the actual story.

A last caution is to be thoughtful about word choice that might be cliche, insensitive, or both. An example that comes to mind is pretty much anytime authors have characters insulted based on their weight. Whatever the writer's intentions, which I mostly believe aren't deliberately nasty, there aren't any weight-based insults that are fresh or that make the insult-er come out the better (though it works if the goal is to show the insensitive speaker's flaws). I also want to warn against insults or jokes based on mental illnesses and disorders, especially because these often popularize ideas of the given disorder that are simply untrue. While a copyeditor can and should be able to gently point out these instances, it avoids awkwardness when an author is able to self-edit and pick different phrasing on their own.

Thursday, September 3, 2015

The Big List of Writing Writing Resources, Part One

You can write your story with nothing but a reasonably flat surface and something that leaves a mark, but it's a lot easier when you have the right tools. Happily, there are a lot of useful resources out there. Here are some of my favorites.

I encountered a few while writing The Starter Guide for Professional Writers (about which I have exciting news: revisions and expansions are underway for a second edition! The past two years have seen some interesting changes in the publishing landscape, and even perennial advice can benefit from an update, right?). Others are from writer's blogs, apps, 'zines, and books developed since.

This first list includes structural advice to find the right words, put them in the right order, and keep putting them down.

Merriam-Webster.com/ This dictionary is free online, which may have something to do with why it's one of the more common reference dictionaries. Bookmark the site for whenever a word is giving you trouble. For many words it includes not only spelling and definition but synonyms, antonyms, and suggested rhymes.

Note: one thing you won't find in many dictionaries are brand names. For example, Merriam-Webster doesn't give results when I search for for "iPhone." To make sure you're spelling a brand name correctly (in this example, lowercase i and no hyphen), it's a good idea to look it up on the official corporate website.

Visual Dictionary Online - Merriam-Webster's visual dictionary, great for connecting words with images. You may know what a thing looks like but be unsure what to call it--or on the other hand, you might have always been wondering where to find a carburetor on a motorcycle or the calyx of a flower.

Rhymer from WriteExpress -A rhyming dictionary for all sorts of sounds, including beginning rhymes, end rhymes, even interior rhymes!

Tip of My Tongue - For when you almost remember a word, or remember part of a word, and need help searching a dictionary for it. Note this is an algorithm, and it's useful but not always nimble--it took me a few tries to get a word when I knew what I was looking for. I started with gr- and looked for words meaning "awful" (no dice), "scary" (no results here either), and "ugly" (success at last, with my goal word gruesome, but I hoped to get a suggestion for grotesque too, and didn't).

One Look Reverse Dictionary - Somewhere between Tip of My Tongue and a Thesaurus, this website finds concepts related to the words you enter in the search bar. I like the variety of results (and got gruesome, grisly, and grotesque as results when I entered "awful, scary, hideous." As an unexpected result, I also got arson.) Remember, though, to always check the definition and connotations of a word you're unsure of before using it.

The Phrase Finder - A UK website with a subsection for American idioms. Type in a phrase and learn its meaning (or have your spelling and/or pronunciation corrected, as when a search for intensive purposes provides intents and purposes as a result).

Words to describe someone's voice - Ideas to jog your thinking, to show rather than tell a character's emotions, and to add sensory detail (specifically, sound). However, descriptions of a character's voice (or anything) can slow the pace of your story, so use judiciously.

Cheat Sheets for writing body language - As above, this provides tools to show instead of telling, this time with visual cues and action rather than description. I think these can be especially useful for "action beats" to break up dialogue, but as before, use judiciously.

45 ways to avoid using "Very" - Stronger words to consider before using an adverb on a more moderate term. Not all these will work in every story, so combine with a thesaurus and/or dictionary for best results!

50 Writing Tools: Quick List - These are writing techniques at the smallest levels of sentence and word choice. All of them habits worth building. Getting practice at picking the right word and constructing sentences with deliberation will pay off with clearer, more powerful prose.

Varying Your Sentence Structure - Sentences that all begin with the same word (usually "I" or "S/he") or are similar in length or structure can get dull. Luckily, the solutions offered by the Walden University Writing Center are simple and can even be sort of fun to put into practice! It's like Sudoku with clauses. Go ahead, call me a word nerd; I'll take it as a compliment.

Random plot generator - Suggestions for characters, setting, situation, and theme. Sometimes disagreeing with the generator is half the fun--consider beginning a story by saying "I can't write about ___, because..."

The Story Starter - Generates a random opening sentence setting up protagonist, setting, and goal. As with the plot generator, sometimes finding a suggestion that doesn't work can be as helpful as finding one that does. (Although on second thought, I might want to try something with "The hilarious dress designer composed a song in the skyscraper in July to prevent the bloodshed.")

Five Elements of a Story (chart) - A useful brainstorming and organizational tool, especially for developing character arc and motive.

All the things that are wrong with your screenplay in one handy infographic - A professional scriptwriter read 300 scripts and kept track of why he passed on 203 of them (as well as providing interesting breakdowns on things like gender of protagonist, genre, and setting). Even if you're not a scriptwriter, the insight into storytelling, craft, and cliche may prove enlightening (encouraging, even?).

How Not to Write a Novel (book) - A humorous, enlightening, and sometimes painful guide to many different ways a manuscript can go wrong, mercilessly covering everything from missteps in characterization and poor decisions in premises to failures in plotting. Complete with illustrative and side-splitting "excerpts."

I encountered a few while writing The Starter Guide for Professional Writers (about which I have exciting news: revisions and expansions are underway for a second edition! The past two years have seen some interesting changes in the publishing landscape, and even perennial advice can benefit from an update, right?). Others are from writer's blogs, apps, 'zines, and books developed since.

This first list includes structural advice to find the right words, put them in the right order, and keep putting them down.

Finding the right words:

Note: one thing you won't find in many dictionaries are brand names. For example, Merriam-Webster doesn't give results when I search for for "iPhone." To make sure you're spelling a brand name correctly (in this example, lowercase i and no hyphen), it's a good idea to look it up on the official corporate website.

Visual Dictionary Online - Merriam-Webster's visual dictionary, great for connecting words with images. You may know what a thing looks like but be unsure what to call it--or on the other hand, you might have always been wondering where to find a carburetor on a motorcycle or the calyx of a flower.

Rhymer from WriteExpress -A rhyming dictionary for all sorts of sounds, including beginning rhymes, end rhymes, even interior rhymes!

Tip of My Tongue - For when you almost remember a word, or remember part of a word, and need help searching a dictionary for it. Note this is an algorithm, and it's useful but not always nimble--it took me a few tries to get a word when I knew what I was looking for. I started with gr- and looked for words meaning "awful" (no dice), "scary" (no results here either), and "ugly" (success at last, with my goal word gruesome, but I hoped to get a suggestion for grotesque too, and didn't).

One Look Reverse Dictionary - Somewhere between Tip of My Tongue and a Thesaurus, this website finds concepts related to the words you enter in the search bar. I like the variety of results (and got gruesome, grisly, and grotesque as results when I entered "awful, scary, hideous." As an unexpected result, I also got arson.) Remember, though, to always check the definition and connotations of a word you're unsure of before using it.

The Phrase Finder - A UK website with a subsection for American idioms. Type in a phrase and learn its meaning (or have your spelling and/or pronunciation corrected, as when a search for intensive purposes provides intents and purposes as a result).

Words to describe someone's voice - Ideas to jog your thinking, to show rather than tell a character's emotions, and to add sensory detail (specifically, sound). However, descriptions of a character's voice (or anything) can slow the pace of your story, so use judiciously.

Cheat Sheets for writing body language - As above, this provides tools to show instead of telling, this time with visual cues and action rather than description. I think these can be especially useful for "action beats" to break up dialogue, but as before, use judiciously.

45 ways to avoid using "Very" - Stronger words to consider before using an adverb on a more moderate term. Not all these will work in every story, so combine with a thesaurus and/or dictionary for best results!

50 Writing Tools: Quick List - These are writing techniques at the smallest levels of sentence and word choice. All of them habits worth building. Getting practice at picking the right word and constructing sentences with deliberation will pay off with clearer, more powerful prose.

Varying Your Sentence Structure - Sentences that all begin with the same word (usually "I" or "S/he") or are similar in length or structure can get dull. Luckily, the solutions offered by the Walden University Writing Center are simple and can even be sort of fun to put into practice! It's like Sudoku with clauses. Go ahead, call me a word nerd; I'll take it as a compliment.

Finding ideas for plot and story structure:

The Story Starter - Generates a random opening sentence setting up protagonist, setting, and goal. As with the plot generator, sometimes finding a suggestion that doesn't work can be as helpful as finding one that does. (Although on second thought, I might want to try something with "The hilarious dress designer composed a song in the skyscraper in July to prevent the bloodshed.")

Five Elements of a Story (chart) - A useful brainstorming and organizational tool, especially for developing character arc and motive.

All the things that are wrong with your screenplay in one handy infographic - A professional scriptwriter read 300 scripts and kept track of why he passed on 203 of them (as well as providing interesting breakdowns on things like gender of protagonist, genre, and setting). Even if you're not a scriptwriter, the insight into storytelling, craft, and cliche may prove enlightening (encouraging, even?).

How Not to Write a Novel (book) - A humorous, enlightening, and sometimes painful guide to many different ways a manuscript can go wrong, mercilessly covering everything from missteps in characterization and poor decisions in premises to failures in plotting. Complete with illustrative and side-splitting "excerpts."

Writing a scene and incorporating details:

11 Steps to Writing a Scene - A sort of checklist that can be helpful either while plotting a scene out (as part of a larger story outline or just before you write a particular section) or editing one.

Dos and Don'ts of Adding More Description - Some general (it not universal) advice for when you might want to expand on a scene, and when not.

Remember, description can be active. When possible, it should be. Watch for overusing "to be" verbs. She was sad, gut-wrenchingly sad, more miserable than she had ever been in her life can become more convincing spelled out: Sobs ripped through her throat until it was raw. She dropped her mother's beloved porcelain dog, dropped the dust rag, and curled up on the floor, not caring for once about getting grime on her jeans. If anyone asked, she could blame her wet, red eyes on the dust. Assuming she was ever going to move on from this room.

On the other hand, it doesn't have to. Maybe you don't want to spend that much time describing your character's grief as she cleans her late mother's home. Readers will grasp that it's a difficult time for her. (Personal confession: I love to indulge in description.)

All the same, it can be useful to find ways to show rather than tell--which remains popular writing advice for a reason. Along with some earlier-mentioned resources, these Cheat Sheets for Writing Body Language can help communicate emotion more effectively and in ways unique to each character.

5 Ways to Increase/Decrease Suspense in Your Writing - A blogger's thoughts on how to draw out suspense or to decrease it. At first I was skeptical why anyone would want to decrease suspense, but the "decreasing" advice looks quite good as a way to build irony, use subtlety, and sometimes move the story along at a faster pace.

I hope these resources make your job a little easier! My next posts will include links for brainstorming plot ideas, self-editing, understanding what goes on in a slush pile, and even creating an audiobook.

Dos and Don'ts of Adding More Description - Some general (it not universal) advice for when you might want to expand on a scene, and when not.

Remember, description can be active. When possible, it should be. Watch for overusing "to be" verbs. She was sad, gut-wrenchingly sad, more miserable than she had ever been in her life can become more convincing spelled out: Sobs ripped through her throat until it was raw. She dropped her mother's beloved porcelain dog, dropped the dust rag, and curled up on the floor, not caring for once about getting grime on her jeans. If anyone asked, she could blame her wet, red eyes on the dust. Assuming she was ever going to move on from this room.

On the other hand, it doesn't have to. Maybe you don't want to spend that much time describing your character's grief as she cleans her late mother's home. Readers will grasp that it's a difficult time for her. (Personal confession: I love to indulge in description.)

All the same, it can be useful to find ways to show rather than tell--which remains popular writing advice for a reason. Along with some earlier-mentioned resources, these Cheat Sheets for Writing Body Language can help communicate emotion more effectively and in ways unique to each character.

5 Ways to Increase/Decrease Suspense in Your Writing - A blogger's thoughts on how to draw out suspense or to decrease it. At first I was skeptical why anyone would want to decrease suspense, but the "decreasing" advice looks quite good as a way to build irony, use subtlety, and sometimes move the story along at a faster pace.

Just Writing:

When you need to get words out, Write or Die and Written Kitten offer negative and positive reinforcement, respectively, for typing some. And typing some more. If you fail to meet the wordcount goal you set, you either miss out on a cute kitten picture--or get your ears blasted by an unpleasant noise. Or even more creative rewards/punishments. Whatever works!

Help! For Writers by Roy Peter Clark (book) offers a lot of suggestions for troubleshooting your way through writer's block, disorganization, and confusion. While Clark's focus and specialty is writing non-fiction articles, I think much of his advice travels well to other forms and genres.

The Varied Emotional Stages of Writing a Book - At least you know that feeling, whatever you're feeling, is normal.

The Varied Emotional Stages of Writing a Book - At least you know that feeling, whatever you're feeling, is normal.

I hope these resources make your job a little easier! My next posts will include links for brainstorming plot ideas, self-editing, understanding what goes on in a slush pile, and even creating an audiobook.

Monday, August 10, 2015

"The Grace of Turning Back" at Beneath Ceaseless Skies

"The Grace of Turning Back," the final story of the Curse-Strewn World sequence, appears in Beneath Ceaseless Skies Issue #179, which can be read on the BCS website or in the Kindle store.

You'll have to read to find out, but I will say writing the ending of this one had me tearing up more than once. Maybe because I'm sentimental, maybe because the Palisades Library (where my friend got me in Tuesday evenings for weekly writing parties) was very dry, who can say?

Also, [slight spoiler follows] for those of you curious to see how a Grace with six wings might look, this gorgeous piece by Rebecca Yanovska might help provide an idea. I didn't see it until I was into the editing process, but when I did I had that feeling of recognition.

I'm very grateful to Scott Andrews at Beneath Ceaseless Skies for publishing the Curse-Strewn World stories, and of course to all of you for reading along with them!

While "The Grace of Turning Back" brings Aniver and Semira's stories to a conclusion, it isn't necessarily the last we'll ever see of them. Two prequel pieces are in my drafts notebook--"The Queen of Yesterday," referenced in "The Storms in Arisbat," has an interesting tale to tell, and of course there's the story of how Aniver and Semira met in the first place on The Glass-Clear Sea.

I can't promise I'll be able to smuggle a secondary-world version of the Sunk Cost Fallacy into those, but I'll surely have fun trying.

The Tynesi merchants, who traded everything from the silver rice of Timru and perfume leaves from Simrandu to chips of ivory off the Keld’s temples, had a term for a particular sort of improvidence: to throw money, time, or strength into seeing to completion a bargain they had already got the worse end of. It’s all After-Bad, they’d say.Has Aniver thrown so much of himself away After-Bad that he has nothing left for his last great spell, returning Nurathaipolis and her sister cities to their proper place in time? At what cost? Can Semira help him without losing herself, too?

A useful phrase. Aniver vaguely remembered his clearheaded pleasure at first learning it.

That pleasure blossoming within his soul had been sacrificed to fuel a magelight to chase away Semira’s nightmares as they approached the edge of the world. It hadn’t meant much to him, had not made up more than a candlelight’s worth of his being, but Aniver was down to the dregs of his power now. And he was draining those dregs, perhaps After-Bad, but he didn’t think they would do much good where he was going.

You'll have to read to find out, but I will say writing the ending of this one had me tearing up more than once. Maybe because I'm sentimental, maybe because the Palisades Library (where my friend got me in Tuesday evenings for weekly writing parties) was very dry, who can say?

Also, [slight spoiler follows] for those of you curious to see how a Grace with six wings might look, this gorgeous piece by Rebecca Yanovska might help provide an idea. I didn't see it until I was into the editing process, but when I did I had that feeling of recognition.

I'm very grateful to Scott Andrews at Beneath Ceaseless Skies for publishing the Curse-Strewn World stories, and of course to all of you for reading along with them!

While "The Grace of Turning Back" brings Aniver and Semira's stories to a conclusion, it isn't necessarily the last we'll ever see of them. Two prequel pieces are in my drafts notebook--"The Queen of Yesterday," referenced in "The Storms in Arisbat," has an interesting tale to tell, and of course there's the story of how Aniver and Semira met in the first place on The Glass-Clear Sea.

I can't promise I'll be able to smuggle a secondary-world version of the Sunk Cost Fallacy into those, but I'll surely have fun trying.

Friday, May 8, 2015

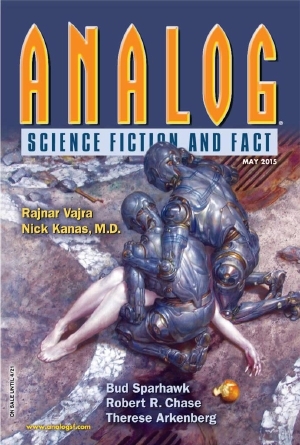

"Arnheim's World" in Analog Magazine

In the May 2015 issue of Analog Science Fiction and Fact, alongside fiction from Rajnar Vajra, But Sparhawk, Robert R. Chase, Aubry Kae Anderson, and J.L. Forrest, my story "Arnheim's World" explores the economics, ethics, and (anti)sociability of terraforming.

Environment, economics, ethics, all stewing in a high-tension dilemma. Exactly the kind of thing you'd expect of me, I hope.

I worked on this piece on and off from 2011 onward, intrigued by the idea of a person wealthy enough and motivated enough to shape a planet in their own image. The plot changed direction several times as I incorporated new concepts and found myself drawn towards one character's argument or another's as they addressed the central conflict. A lot of my science fiction stories deal with dilemma, and until I find a resolution that satisfies me they can sit unfinished for a long time. Mind, just because I pronounce myself satisfied with a story's ending doesn't mean I think any one character made the right decision--just that I sympathize with them all and find the outcome of events pleasingly...twisty. Or twisted. Sometimes I write an ending I find myself hoping readers will argue with (I still remember reading along with TV Tropes, trying to find loopholes to 'fix' "The Cold Equations").

For "Anheim's World," I think the conflict that most preoccupied me is less about economics than about friendship and betrayal--and times when betraying a friend may be the nobler decision.

You be the judge.

Tuesday, February 24, 2015

Common edits to improve your writing

A lot of editing and rewriting involves relatively minor mechanical and technical changes. A lot. Not that I'm complaining; making these simple changes is a routine part of my work, and if nothing else it keeps me steadily employed. Many of them are changes I make to my own writing on a second draft!

However, I thought it'd be helpful to share my "greatest hits": the advice I give most often, and make use of most often when revising my own work. If you can apply this advice to your own manuscript, it will become noticeably cleaner. This doesn't mean it'll be perfect--but once a story is polished technically, it can be easier to spot and address more subtle or individual strengths and weaknesses. If a manuscript is full of run-on sentences, it can be hard to even follow the plot, much less worry about how it meshes with the character arcs!

However, I thought it'd be helpful to share my "greatest hits": the advice I give most often, and make use of most often when revising my own work. If you can apply this advice to your own manuscript, it will become noticeably cleaner. This doesn't mean it'll be perfect--but once a story is polished technically, it can be easier to spot and address more subtle or individual strengths and weaknesses. If a manuscript is full of run-on sentences, it can be hard to even follow the plot, much less worry about how it meshes with the character arcs!

- Which brings me to my first bit of advice, and the one tidbit of information that has been most useful to me personally this past year: the average sentence should be about 20 words long. Some will be shorter. Others will be much longer. You'll want to manage longer sentences carefully (especially if they're over 30 words), and you probably won't want to use more than one or two per paragraph. The first sentence in this bullet point is 35 words long; the third is 27.

- Check to make sure that a long sentence isn't in fact a run-on or a comma splice. I don't think you need to be a grammar expert to be a good storyteller. However, being able to write clear sentences is important to allow readers to follow along. Also, being able to spot and fix run-on sentences (as well as to avoid writing many of them in the first place) will save you immense amounts of time on your second draft--and, if you hire an editor, a manuscript with fewer sentence boundary errors to correct will save you money, too.

- When it comes to sentence boundary errors and sentence structure issues, such as parallel structure, I encourage all writers to approach them humbly. Overconfidence about my ability to write a clean sentence meant that I've taken a long time to acknowledge and fix several of my most awkward habits. I'm still catching myself using poetic comma splices or abandoning parallel structure without good reason. I suspect I'm not alone in my overconfidence, either, because sentence boundary errors are the single issue with manuscripts that I spend the most time fixing.

- One method to catch run-on sentences, which also is an excellent method to study your word choice and voice in general, is to read the story aloud. Listen to the places you pause--for effect or for breath--and try to make them match the punctuation on the page. Raise your voice when you write a question mark (which should only go after a direct question). Only take a breath at periods/full stops (and shorter breaths at semicolons, shorter still at commas). Learning to read aloud was an important part of my own long education in the fact that, hey, I really do write too many long sentences!

- The English language is not like German--it's likely that far fewer nouns need to be capitalized than you might think. That is, I more often have to put nouns in lowercase than I do capitalizing them in the manuscripts I edit. Some of these excess capitals may be hypercorrection (the same thing that causes people to say 'whom' instead of 'who' in the wrong sentence, or to say 'I feel badly' rather than 'I feel bad'). I believe you can trust your gut here. Unless a word would look distressingly wrong without the capitalization, it’s probably just fine in lowercase.

- However, if you don't trust your gut, here's a handy rule of thumb: a noun is capitalized if it names a unique item (the Thames river, the Story Addict blog) or is being used as part of a name (I thanked my doctor by saying "I'll never be able to repay you, Doctor Barnes"; I told my mother, "Good morning, Mom"). If not, then probably not. Note that 'Mom' is capitalized when it's addressing the mother, but lowercase otherwise. I was excited to hear Aunt Janie was coming for a visit. -vs - Her aunt, Janie, came to visit that weekend.

- Dialogue can appear clunky when it's always tagged in the same way. By this, I don't mean to encourage using "said-bookisms"-- "said" is a clear and invisible word. However, every line of dialogue does not need to be prefaced by "Character Name Said." That makes a manuscript look like a screenplay. Also, consider using a variety of dialogue tags--sometimes "Character name said" and sometimes "said Character Name" (odd as it sounds, I've read manuscripts that only used the latter form, and it invariably began to sound awkward). Sometimes action beats instead. The variety will keep a conversation lively and interesting to follow. However, dialogue tags that are awkward, unnecessary, or repetitive can distract a reader so much that it ruins the entire scene.

- Be careful of the phrase "and said". Often this is superfluous--readers will assume that the character who performs an action beat is also the speaker within the same paragraph (on which note, remember to start a new paragraph each time there's a new actor or speaker). Occasionally, adding "and said" will produce a sentence that overstays its welcome in an anticlimax--She felt her world crashing down around her, leaving behind only a hollow emptiness, a chilly void like she'd never felt before, and said, "I'm so unhappy."

- In general, "and" sometimes links information within a sentence that doesn't need to be linked (a made-up example I enjoy sharing is She was crying on the stairway all night and she had never liked getting takeout, anyway.)

- Speaking of connecting information and avoiding anticlimax or bathos: details of character action, emotion, dialogue, and inner monologue should be carefully chosen to contribute to a particular mood and communicate specific ideas. Be careful of language that might be distracting or carry connotations you don't intend. Synonyms rarely mean the exact same thing.

- I always highlight repeated words in manuscripts. It's a good idea to avoid repeating the same word within a brief amount of space unless it is necessary to make a point or communicate clearly. Depending on how unique a word sounds, and thus how memorable or noticeable it is, I suggest avoiding an echo of it within the same sentence (always), within two adjacent sentences (usually), within a single paragraph, or even within a full page or entire chapter. Likewise avoid repeating the same figure of speech.

- Some of the most common verbs I find myself highlighting are turning/turned, looking/looked, walking/walked, and smiling/smiled. Some writers attack the problem of characters turning, looking, walking, and smiling too much by using synonyms, which is good for word variety but may still lead to characters behaving in eerily repetitive ways. Consider cutting some instances of these words and synonyms, but also consider when different word choice would be stronger. She looked at her mother angrily could become She glared at her mother. Likewise, She walked towards him could be She approached him or She stalked towards him depending on the nature of the scene. And lastly, these verbs can be unnecessary within context. Characters can be assumed to have turned to the person they're addressing (if they haven't, this is worth mentioning), to have looked at an object the narrative in their point of view is describing, or to have walked to the room they come into.

- A weird fact: 'blond/e' is one of very few English words that is gendered. Men are never blonde, they are blond.

- Dialogue is considered part of the same sentence as the dialogue tag. “She said” is not a complete sentence. It should be connected to the line of dialogue by a comma. Capitalize appropriately. This one is worth stressing, being perhaps the second most common error I correct, and common among manuscripts that are otherwise very polished.

- I have a personal preference for showing only dialogue in quotation marks, and putting all other communication (such as written text the characters are reading) in italics. There isn’t complete consensus on this, though. All the same, I suggest avoiding reader confusion by never using quotation marks for a character's unspoken inner monologue. Instead, use italics (I thought, this story is harder to understand than I expected. I muttered to myself, "I could write a blog post about this."). The risk here is making it look like your character has just called his boss an unprintable word aloud, and readers will wonder why he isn't being fired.

- Passive voice is to be avoided except for when there is a specific reason in favor of using it. Aside from being verbose, passive voice obscures the identity of whoever is performing the action, adding an unnecessary air of mystery (except for when the writer uses passive voice to build an air of mystery very deliberately). Passive voice can also blur the line between action and description--was the ladder set against the wall when they entered the room, or is the protagonist leaning it there right now?

- Filters such as I thought, I felt, I heard, and I remembered are often unnecessary, and can be cut unless they contribute to clarity or sentence rhythm.

- It's common advice to "show" rather than "tell," but it's important to focus on "showing" the most important details (it is the storyteller's privilege and duty to decide what details are most important to the story). Use "telling" to communicate information that needs to be known to make sense of the story, but isn't dramatic or significant enough for showing. If a detail doesn't really add to the story, you don't need to mention it at all unless you want to.

- Melodrama is a matter of personal taste. In general, though, I believe most manuscripts benefit from making use of subtly and having extreme and intense moments stand out because of their rarity. If every character screams their dialogue in every scene, it becomes harder to tell when a disagreement is really serious. If a character bursts into tears over failing to find a parking space, it'll be a struggle to show how much worse the character feels when Aunt Janie goes missing.

- Once information is shown or told, it won't need to be introduced again, although it may be referred to as the character has cause to remember it. Outlining can help you keep track of when you introduced specific information, and that will keep you from repetition that leaves the reader thinking "Yes, I know already, get on with it!" Rereading will also help catch this.

- Nobody wants to think they have unwarranted tense changes in their first draft--but it's quite likely that you do. I almost always do, because I write my outlines in present tense and most of my fiction in the past tense. Sometimes when an author gets caught up in the moment, they switch into present tense. And authors who intend to write an entire story in present tense will sometimes slip up and use past. Luckily, this is usually quite simple to fix; just be aware that this happens so you aren't caught unprepared.

- Always look up the spelling of brand names, trademarks, and websites. They tend to be idiosyncratic. Also, once you've looked them up, ignore Autocorrect when it tries to tell you differently.

- Speaking of looking up spelling, the Merriam-Webster dictionary is free online, and can be very useful to check spelling and to make sure a word means exactly what you're using it for. Bookmark it.

- Merriam-Webster will sometimes give you multiple ways to spell a word, especially when it comes to hyphenated ones (although as a quick rule of thumb, adjectives are often hyphenated when nouns are not. He's a blue-eyed boy with blue eyes.) Once you decide on a preferred spelling, you may want to make a note of it on a 'style sheet.' This is also a good way to keep track of formatting decisions (such as whether you spell out numbers or use digits--fiction writing leans towards spelling out most numbers under 1,000--and whether or not you're using the serial/Oxford comma). Copyeditors make style sheets for each manuscript they're working with. They don't have to be fancy. A Post-It note over your laptop that reads "always use hyphen when M-W.com says so; spell one-nine hundred ninety nine and write 1,000<; no Oxford comma; A.M. and P.M." does the job as well.

- Metaphors are an area of great risk and great reward. Some people don't think in analogies at all, while others live in a parallel world populated by associations. I'm in the latter group myself, and I enjoy rich, poetic metaphors that build a story thematically and use language in fun ways. However, be careful of cliches, and do make sure your metaphors fit the tone and setting of the story (“The death of Romeo set Juliet on an emotional roller coaster.”)

- And lastly, a piece of advice for being edited: it will take time, but be sure to look over each change as you accept it. I always try to protect the voice of each writer, but sometimes I'll rewrite a sentence to offer an example. Or I'll suggest several different changes, and the author can pick the one that fits their story best. Perhaps I'll suggest something that absolutely clashes with the story's goals, and the author will have to click the "Reject Change" button. That said, editors do try hard to make a story the best it can be, and we don't make our suggestions lightly. If you're rejecting every change an editor suggests, consider why that is. Possibly your styles don't mix--but it's not a sign of disparagement for your original authorial voice to correct run-on sentences or suggest you double check the spelling of a word. Be an active partner in polishing your story, and you, your editor, and your readers will be better off from it.

- A lot of what I learned about writing I learned from being edited. I also learned a lot about writing by helping to edit others' work (both in critique groups and even now, as a professional editor). I learned several things about writing by carefully reading others' stories, both published and unpublished. And I learned a lot about writing from, well, writing! Never let pass an opportunity to learn. Reading, writing, and rewriting will also help you think more about stories and give you inspiration for your next work.

Thursday, January 22, 2015

"For Lost Time" up at Beneath Ceaseless Skies

Lose no time in going to check out the latest installment in Across the Curse-Strewn World, a short story sequence following the wizard Aniver and his friend Semira's quest to rescue his home city, which has somehow become lost in time.

Their discoveries in the terrifying library of Arisbat have pointed Aniver and Semira in the right direction, but what a direction it is--the source of the blight that struck Nurathaipolis appears to have come from the Kingdom of the Dead. Aniver's reckless plan requires that he scout out the territory first...

"For Lost Time" appears in Beneath Ceaseless Skies Issue #165, and can be read on the BCS website or on Kindle.

Their discoveries in the terrifying library of Arisbat have pointed Aniver and Semira in the right direction, but what a direction it is--the source of the blight that struck Nurathaipolis appears to have come from the Kingdom of the Dead. Aniver's reckless plan requires that he scout out the territory first...

"For Lost Time" appears in Beneath Ceaseless Skies Issue #165, and can be read on the BCS website or on Kindle.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)